Thanks For The Free Ride

In modern day life, almost every imaginable human activity seems to be governed by a body of law and/or regulation. In baseball, a batter is out when a third strike is caught. The driver of a vehicle must come to a complete stop at a stop sign. We are required by law to pay taxes by filing a yearly tax return. Building codes govern home construction. By law, no smoking is allowed on airplanes. The list of examples is practically infinite. We all have become habituated to living lives within limits set by law.

Since laws and regulations are only printed words on paper without enforcement, every system of laws and regulations requires law enforcers. Thus, we have also become accustomed to the presence of law enforcers in our everyday lives. Umpires, referees, police officers, IRS agents, city inspectors, and many other types of law enforcers permeate our society.

Judges are needed to ensure that laws and regulations are enforced fairly. Nevertheless, judges are required to follow the law.

So the mere existence of laws and regulations creates three general classes of participants; those who are subject to the laws and regulations, those who are charged with enforcing the laws and regulations and those who are charged with adjudicating controversies over the application of laws and regulations.

In my experience as a judge, I quickly realized that the relationship of the law enforcers and those who are subject to law enforcement is not necessarily acrimonious or hostile.

Legitimate law enforcement is not personally adversarial or based on characterization or labelling of individuals according to any standard that exists outside of the law being enforced. A little league baseball umpire once told me that, in response to an angry parent who vehemently tried to defend a player who had been called out, he reminded the enraged parent that the youngster was not a bad kid. He was just “out.”

Further reflection on the relationship of participants brought together through the law inspired the realization that my purpose on the bench is not to sit in judgement of anybody as a good or bad person, but simply to get the facts right and apply the law to the facts; nothing more, nothing less.

If law enforcement is performed legitimately and properly people will respect the outcome, or at least understand that the law is governing the law enforcement and adjudication; not the law enforcer or the judge.

Also, law enforcement is a two edged sword. In other words, legitimate law enforcement not only consists of maintaining limitations. Law enforcement also requires granting benefits provided by law to those who are qualified for such benefits.

In this respect, the immigration laws are no different than any other system of laws.

Sometimes, it seems that in the raging debate over immigration law many seem to overlook the fact that immigration law enforcement consists not only of denying applications and deporting people, but immigration law enforcement also includes granting of benefits provided by law.

Remember Thomas Jefferson’s comment about the proper function of judges:

Let mercy be the character of the law giver, but let the judge be a mere machine. The mercies of the law will be dispensed equally and impartially to every description of men; those of the judge, or the executive power, will be the eccentric impulses of whimsical, capricious designing man.

(Letter to Edmund Pendleton, August 13, 1776)

A plethora of benefits, waivers, visas and relief from removal exists in United States immigration law.

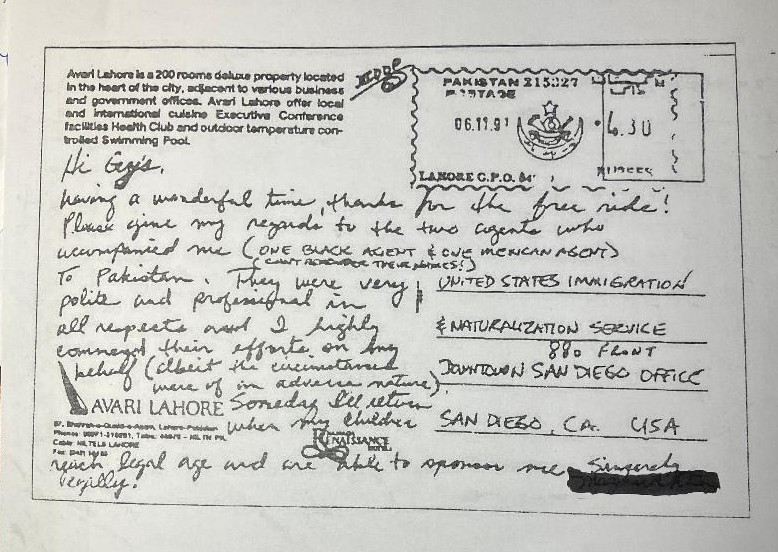

In addition, not everyone who is removed from the United States due to illegal immigration status harbors animosity from the denial of benefits or even deportation, as long as they feel that they were respected as individuals and received fair treatment.