Sufficiency of a Defective NTA to Establish Jurisdiction and Revoke Parole Status

On September 23, 2021, the Board of Immigration Appeals (“BIA”) published a decision in which it holds that:

- A Notice to Appear that does not specify the time and place of a respondent’s initial removal hearing does not amount to a jurisdictional defect that deprives an Immigration Judge of jurisdiction over a respondent’s removal proceeding; and

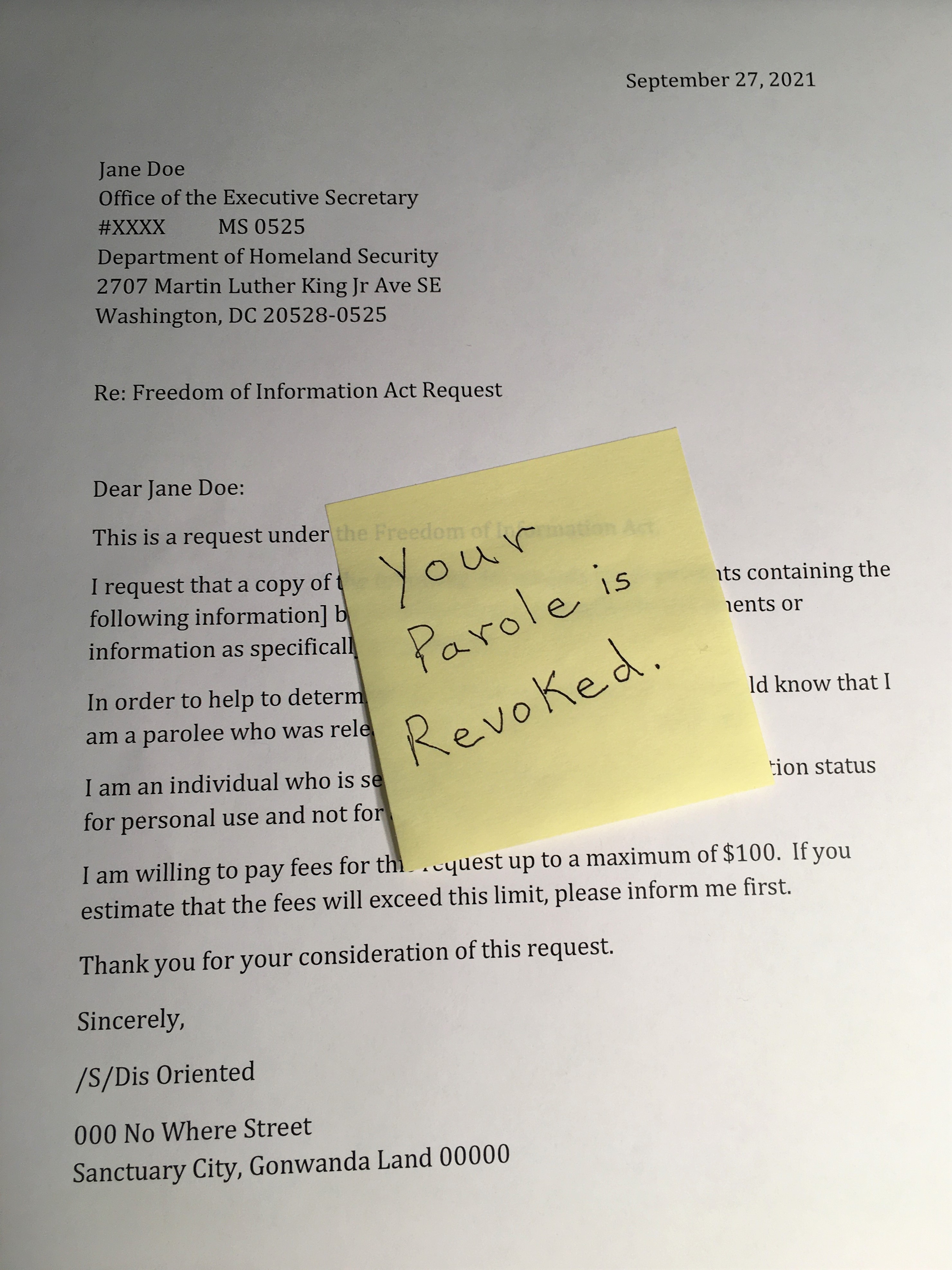

- A Notice to Appear that lacks the time and place of a respondent’s initial removal hearing is sufficient to terminate an alien’s grant of parole under 8 C.F.R. § 212.5(e)(2)(i).

See Matter of Arambula-Bravo, 28 I&N Dec. 388 (BIA 2021).

The procedural history, facts of record, holding and rationale in Matter of Arambula-Bravo, 28 I&N Dec. 388 (BIA 2021) are as follows:

Case History

The respondent was granted parole on October 23, 2009, scheduled to expire on April 20, 2010.

On February 12, 2010, the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) served her with a Notice to Appear (“NTA”).

The Immigration Judge held that the respondent’s parole terminated upon the February 12, 2010 service of the NTA, rendering her removable as charged under section 212(a)(6)(A)(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended (“the Act”) (i.e. noncitizen present in the United States without being admitted or paroled, or who arrived in the United States at any time or place other than as designated by the Attorney General).

Ultimately, the Immigration Judge ordered the respondent removed from the United States.

The respondent filed a notice of appeal.

Facts

The respondent is a native and citizen of Mexico who has twice been previously removed under a different name and Alien Registration Number.

Following a September 2008 arrest for unlawfully transporting aliens into the United States in violation of sections 274(a)(1)(A)(ii) and (v)(II) of the Act the respondent was granted parole on October 23, 2009.

The NTA, served by the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) on February 12, 2010, ordered the respondent to appear before an Immigration Judge at a time and date “to be set.”

Six days later, a notice of hearing was mailed to the respondent, providing her with the time, date, and place of her initial removal hearing, at which she appeared.

The Immigration Judge held that the respondent’s parole terminated upon service of the NTA (on February 12, 2010) and rendered her removable.

The Immigration Judge then concluded that the respondent’s criminal conviction was an aggravated felony, which resulted in ineligibility for cancellation of removal and voluntary departure. See sections 240A(b)(1)(C), 240B(b)(1)(C) of the Act; see also section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the Act.

The Immigration Judge also determined that the respondent was ineligible for adjustment of status because she was inadmissible to the United States. See section 245(a)(2) of the Act.

Held

Appeal Dismissed

Rationale

Jurisdiction

- As noted in Matter of Bermudez-Cota, 27 I&N Dec. 441, at 443 (BIA 2018), the “narrow” holding of Pereira v. Sessions, 585 U. S. ___ (2018) specifically related to the “stop-time” rule, and we observed that “the Court did not purport to invalidate the [noncitizen’s] underlying removal proceedings or suggest that proceedings should be terminated.”

- While 8 C.F.R. § 1003.14(a) (2018) states that “[j]urisdiction vests . . . when a charging document is filed,” the regulation did not specify what information must be included in the “charging document” or mandate that the document specify the time and place of the removal hearing before jurisdiction will vest. Matter of Bermudez-Cota, at 444–45.

- Specific rules regarding the initiation of proceedings in 8 C.F.R. § 1003.14 are “claim-processing” rules that do not implicate the subject matter jurisdiction of the Immigration Court. Matter of Rosales Vargas and Rosales Rosales, 27 I&N Dec. 745, at 751–52 (BIA 2020); see also Karingithi v. Whitaker, 913 F.3d 1158, at 1161-62 (9th Cir. 2019) (deferring to Matter of Bermudez-Cota and holding that the Immigration Judge had jurisdiction even though the NTA did not specify the time and date of the removal proceedings).

- Every court of appeal that has considered the question has agreed that a "Notice to Appear" that lacks information required by section 239(a) of the Act is sufficient to vest the Immigration Court with subject matter jurisdiction. Ali v. Barr, 924 F.3d 983, at 986 (8th Cir. 2019); see also Gonçalves Pontes v. Barr, 938 F.3d 1, at 5–7 (1st Cir. 2019); Banegas-Gomez v. Barr, 922 F.3d 101, at 110–12 (2d Cir. 2019); Nkomo v. Att’y Gen. of U.S., 930 F.3d 129, at 133–34 (3d Cir. 2019); United States v. Cortez, 930 F.3d 350, at 358–62 (4th Cir. 2019); Maniar v. Garland, 998 F.3d 235, at 242 (5th Cir. 2021); Santos-Santos v. Barr, 917 F.3d 486, at 489–91 (6th Cir. 2019); Ortiz-Santiago v. Barr, 924 F.3d 956, at 958, 962–64 (7th Cir. 2019); Karingithi, 913 F.3d at 1161–62; Lopez-Munoz v. Barr, 941 F.3d 1013, at 1015–18 (10th Cir. 2019); Perez-Sanchez v. U.S. Att’y Gen., 935 F.3d 1148, at 1153–57 (11th Cir. 2019).

See Matter of Arambula-Bravo, at 389-92

Parole Termination

- Under 8 C.F.R. § 212.5(e)(2)(i), the service of a “charging document” on a noncitizen constitutes “written notice of termination of parole.”

- The NTA is one among other documents described as a “charging document” in 8 C.F.R. § 1003.13 (2021) as “the written instrument which initiates a proceeding before an Immigration Judge.”

- Therefore, the charging document in this case—a putative NTA—was sufficient to terminate the respondent’s grant of parole under 8 C.F.R. § 212.5(e)(2)(i).

- There is no reference to section 239(a) in 8 C.F.R. § 1003.13.

- Notice of the time and place of an initial removal hearing, while essential to the NTA’s function in commencing removal proceedings, is not essential to the NTA’s function as a notice of termination under 8 C.F.R. § 212.5(e)(2)(i) because Immigration Judges have no authority to review DHS decisions relating to the grant or revocation of parole. Thus, no hearing is required that necessitates notice of the time and place of an initial hearing.

- Furthermore, because no hearing is required to terminate parole, the function of the section 239(a) requirements in facilitating the right to counsel is also diminished.

- Adopting a rule that the effectiveness of an NTA in terminating parole turns on whether it contains information concerning a subsequent, unrelated removal hearing—at which the Immigration Judge would have no authority to review the grant of parole or its termination—is likely to cause confusion for both parolees and immigration officers.

See Matter of Arambula-Bravo, at 392-96

Commentary

Congress described a Notice to Appear using the following language:

§239 Initiation of removal proceedings

- Notice to Appear

- In General

In removal proceedings under section 240, written notice (in this section referred to as a “notice to appear”) shall be given in person to the alien . . . specifying the following:

- The nature of the proceedings against the alien.

- The legal authority under which the proceedings are conducted.

- The acts or conduct alleged to be in violation of law.

- The charges against the alien and the statutory provisions alleged to have been violated.

- The alien may be represented by counsel and the alien will be provided (i) a period of time to secure counsel . . . and (ii) a current list of counsel . . .

- (i) The requirement that the alien must immediately provide (or have provided) the Attorney General with a written record of an address and telephone number (if any) at which the alien may be contacted respecting proceedings under section 240.

ii. The requirement that the alien must provide the Attorney General immediately with a written record of any change of the alien’s address or telephone number.

iii. The consequences under section 240(b)(5) of failure address and telephone information pursuant to this subparagraph.

- (i) The time and place at which the proceedings will be held.

ii. The consequences under section 240(b)(5) of the failure, except under exceptional circumstances, to appear at such proceedings.

See Section 239(a)(1) of the Act.

Obviously, the BIA has taken the position that in the context of removal proceedings a “notice to appear” that omits information described in section 239(a)(1)(G)(i) of the Act (i.e. “[t]he time and place at which the proceedings will be held”) might be defective, but it still qualifies as “written notice” for the purpose of establishing jurisdiction of the immigration court in which it is filed. Moreover, the BIA cited eleven Courts of Appeal which have agreed that a defective NTA that lacks information required by section 239(a)(1)(G)(i) of the Act is sufficient to vest the immigration court with subject matter jurisdiction.

I’m not sure if any court has specifically entertained the argument that a defective NTA that does not contain all of the specified contents described in section 239(a)(1) of the Act does not meet the NTA definition as a matter of law. In other words, a defective NTA cannot exist because it is a nullity (i.e. it is not an NTA) and cannot constitute “written notice” for the purpose of initiating removal proceedings. It doesn’t seem likely that this argument has gained or would gain traction with regard to omission of the time and place of the initial hearing.

However, omission of factual allegations or charges or both required in section 239(a)(1)(C) and (D) of the Act in a "Notice to Appear" might support a forceful argument that such omission fails to provide sufficient information to the recipient to permit preparation of a defense or response; thus, defeating the purpose of “written notice.” Perhaps, this type of substantive defect would defeat jurisdiction.

I remember at least one removal proceeding in Houston, Texas in which the DHS had served the respondent (i.e. an individual who is the subject of removal proceedings in immigration court) with a proper NTA but never filed it in the immigration court. The DHS subsequently served the respondent with a second NTA containing different allegations and a different charge, and filed the second NTA in the immigration court. The DHS then asserted that filing the first NTA cut off the respondent's physical presence making him ineligible for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1) of the Act, as provided in section 240A(d)(1) of the Act, even though the first NTA had never been filed and the second NTA had been used to initiate removal proceedings. This circumstance, however, presents a different issue (i.e. whether the service of a proper NTA that is not used to initiate removal proceedings triggers the stop-time rule to end continuous physical presence under section 240A(d)(1) of the Act). For readers who are unfamiliar with cancellation of removal, one of the criteria necessary for eligibility is proof that the applicant "has been physically present in the United States for a continuous period of not less than 10 years immediately preceding the date of such application." See section 240A(b)(1)(A) of the Act.

Ultimately, the respondent prevailed and was deemed eligible to apply for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1) of the Act.

With regard to parole revocation, it seems odd that the BIA did not refer to plain language of 8 C.F.R. § 212.5(e)(2)(i) which states that “parole shall be terminated upon written notice to the alien and he or she shall be restored to the status that he or she had at the time of parole.” [emphasis added]

The phrase, “written notice,” in 8 C.F.R. § 212.5(e)(2)(i) could justify a possible DHS position that a written letter or any kind of notice that is committed to writing (as opposed to oral notice) is sufficient to revoke parole status.

For the purpose of parole revocation, “written notice” in 8 C.F.R. § 212.5(e)(2)(i) is not linked to the specified mandatory content of a "Notice to Appear" in section 239(a)(1) of the Act. Nevertheless, if a defective NTA is missing enough substantive mandatory content to be classified as a nullity the DHS might not be able rely on it for parole revocation.

For those who might be interested in immigration law history, it might be enjoyable to consider what seems to be the statutory precursor of parole.

In 1891, Congress specifically provided that a temporary removal of a person from a vessel for inspection is not a “landing” of such person:

That upon the arrival by water at any place within the United States of any alien immigrants it shall be the duty of the commanding officer and the agents of the steam or sailing vessel by which they came to report the name, nationality, last residence, and destination of every such alien, before any of them are landed, to the proper inspection officers, who shall thereupon go or send competent assistants on board such vessels and there inspect all such aliens, or the inspection officers may order a temporary removal of such aliens for examination at a designated time and place, and then and there detain them until a thorough inspection is made. But such removal shall not be considered a landing during the pendency of such examination. [emphasis added]

See section 8 of the Act of March 3, 1891.

To my knowledge, section 8 of the Act of March 3, 1891 contains the first description of parole, even though the word, “parole,” was not used.

By specifically stating that removal of a person from a vessel for the purpose of inspection is not a “landing,” Congress reserved the government’s right to enforce exclusion grounds, as opposed to deportation grounds.

After passage of the Act of March 3, 1891, the inspection process was no longer carried out by officers appointed by state entities, but by inspection officers of the United States. This transfer of duties from nonfederal agencies to the federal government appears similar to the transfer of airport security processing to the Transportation Security Administration in more recent times.

Some readers might be interested to know that the Act of March 3, 1891 directly led to the opening of Ellis Island in New York on January 1, 1892.