Rule of the Last Antecedent

One way to begin explaining how an exception to the rule of the last antecedent influenced the outcome of the Board of Immigration Appeals ("BIA") recent published decision is to set forth the governing facts and procedural history upon which the decision in Matter of Moradel, 28 I&N Dec. 310 (BIA 2001) is based.

The respondent (i.e. the individual who is the subject of immigration court proceedings) is a native and citizen of Honduras, who was born in 1995 and entered the United States without being admitted or paroled when he was approximately 4 years of age.

In 2013 when he was almost 18 years of age, he was placed in removal proceedings and conceded that he was subject to removal.

He subsequently filed a petition to be classified as a Special Immigrant Juvenile as defined under section 101(a)(27)(J) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended ("the Act"), which was approved.

In December 2017, the respondent was convicted for possession of 50 grams or less of marijuana in violation of section 2C:35-10(a)(4) of the New Jersey Statutes Annotated.

The respondent conceded that his conviction rendered him inadmissible under section 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the Act, as an alien convicted of an offense relating to a controlled substance.

Nevertheless, the respondent sought relief from removal in the form of adjustment of status under section 245(a) of the Act by seeking a waiver of the section 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) ground of inadmissibility through application of the waiver for Special Immigrant Juveniles under section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act.

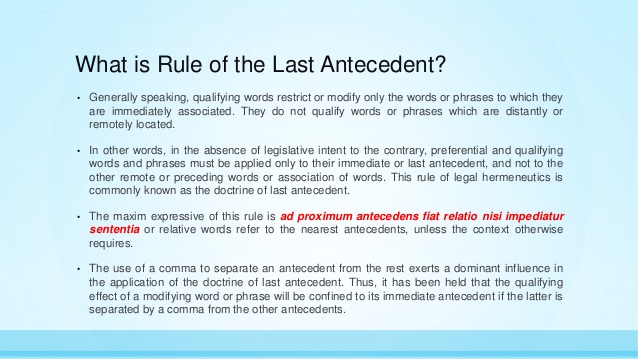

In immigration proceedings, an Immigration Judge determined that the respondent was ineligible for a waiver of inadmissibility under section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act, and thus was ineligible for adjustment of status under section 245(a) of the Act. In support of her decision, the Immigration Judge relied on the rule of the last antecedent. Simply stated, the rule of the last antecedent requires that a limiting clause or phrase should be read as modifying only the noun or phrase that it immediately follows.

The respondent appealed from this decision, asserting that application of the rule of the last antecedent should not apply.

The second issue addressed in Matter of Moradel is whether a categorical (i.e. hypothetical) approach or a circumstance-specific (i.e. fact based) inquiry should be used to determine the amount of possessed controlled substance underlying the respondent's offense for which he had been convicted.

In summary, the issues in Matter of Moradel are as follows:

- Whether the “simple possession” exception described in section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act applies to the ground of inadmissibility under section 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the Act, rather than being limited by the rule of the last antecedent to the ground of inadmissibility under section 212(a)(2)(C) of the Act; and

- Whether a circumstance-specific inquiry (i.e. fact based inquiry) into the underlying facts of the applicant's simple possession offense is appropriate to determine the amount of controlled substance involved, rather than a categorical (i.e. hypothetical) approach.

If the rule of the last antecedent is applied to the parenthetical exception (i.e. "except for so much of such paragraph as related to a single offense of simple possession of 30 grams of marijuana") the parenthetical exception would only apply to the ground of inadmissibility under section 212(a)(2)(C) of the Act. This is true simply because the parenthetical exception immediately follows "(2)(C)" in the same sentence.

Section 212(a)(2)(C) of the Act generally relates to an alien whom the consular officer or the Attorney General knows or has reason to believe is or has been an illicit trafficker in any controlled substance, including aiding and abetting others in such illicit controlled substance trafficking. Whereas, section 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the Act relates to an alien who has committed or has been convicted of any law or regulation relating to a controlled substance; clearly a less egregious offense category.

In brief, with regard to whether the “simple possession” exception described in section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act applies to the ground of inadmissibility under section 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the Act, rather than being limited by the rule of the last antecedent to the ground of inadmissibility under section 212(a)(2)(C) of the Act, the BIA reasoned as follows:

- the last-antecedent rule (i.e. that a limiting clause or phrase should ordinarily be read as modifying only the noun or phrase that it immediately follows) is “not an absolute and can assuredly be overcome by other indicia of meaning.” Paroline v. United States, 572 U.S. 434, 447 (2014);

- under the Immigration Judge’s interpretation, an individual with Special Immigrant Juvenile status with a single conviction for simple possession of 30 grams or less of marijuana would rarely, if ever, qualify for a waiver under section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act, while a person with a more serious trafficking conviction would qualify - an "unlikely premise" that rebuts application of the last antecedent inference rule;

- because simple possession does not qualify as trafficking, the last-antecedent rule would also effectively read the “simple possession” exception out of section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act; and

- therefore, Congress intended the “simple possession” exception in section 245(h)(2)(B) to be applied broadly.

Turning to whether a circumstance-specific inquiry into the facts surrounding an applicant's simple possession offense is appropriate, rather than a more narrow hypothetical approach, the BIA noted that:

- it had previously held that the circumstance-specific approach applies in determining whether, for purposes of a waiver under section 212(h) of the Act, an applicant committed “a single offense of simple possession of 30 grams or less of marijuana.” Matter of Martinez Espinoza, 25 I&N Dec. 118, at 124-25 (BIA 2009);

- in Matter of Martinez Espinoza, 25 I&N Dec. 118, at 124 (BIA 2009) (citing Nijhawan v. Holder, 557 U.S. 29, at 32 (2009)), abrogated on other grounds by Mellouli v. Lynch, 575 U.S. 798 (2015)., it had reasoned that the language of the 212(h) waiver invited a circumstance-specific inquiry under Nijhawan because it “referenc[ed] a specific type of conduct (simple possession) committed on a specific number of occasions (a ‘single’ offense) and involving a specific quantity (30 grams or less) of a specific substance (marijuana).” Matter of Martinez Espinoza, at 124;

- because the “simple possession” exception at section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act contains identical language and is defined just as narrowly as the exception under section 212(h) of the Act, the BIA concluded that it also calls for a circumstance-specific inquiry into the nature of the conduct surrounding an applicant’s simple possession offense; and

- the categorical approach usually applies when the DHS has the burden of proof to establish a removal ground, and in the instant case, the respondent has the burden of proof to establish eligibility for a waiver.

The categorical approach originated as a method for of classifying an offense as an aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43) of the Act. Use of the categorical approach has spread to application in other contexts where the government must carry the burden of proof.

In conclusion, it seems fair to say that Matter of Moradel, broadened the availability of the waiver under section 245(h)(2)(B) of the Act for Special Immigrant Juveniles applying for adjustment of status. However, by rejecting the hypothetical categorical approach and adopting the circumstance-specific fact based approach to determine whether an offense underlying the ground of inadmissibility is a single simple possession of marijuana, Matter of Moradel reduces the number of applicants who will be able to demonstrate eligibility for the waiver.

For more detail, the reader should read Matter of Moradel in its entirety, but hopefully this case brief will serve as a practical guide.