Proving a Negative

On March 4, 2021, Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing for the majority, determined that an alien who had applied for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1) of the Act did not carry the burden of proof that he had not been convicted of a disqualifying offense (i.e. a crime involving moral turpitude ("CIMT")) when the record shows he had been convicted under a statute listing multiple offenses, some of which disqualify him for cancellation of removal (i.e. CIMTs), and the record is ambiguous as to which crime formed the basis of his conviction. Clemente Avelino Pereida, Petitioner v. Robert M. Wilkinson, Acting Attorney General, 592 U. S. ____ (2021) No. 19–438 (slip op., at 1).

As a consequence, an applicant for cancellation of removal, who has been convicted of one or more crimes, must establish for which of the listed crimes the applicant had been convicted to eliminate any listed disqualifying offense.

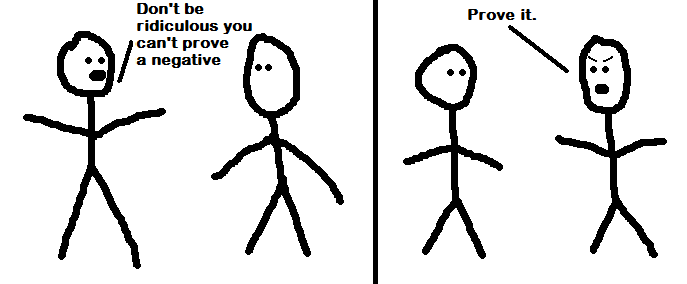

In short, the United States Supreme Court held that under section 240A(b)(1) of the Act, applicants for cancellation of removal must "prove a negative" that they have not been convicted of a disqualifying crime by proving conviction for any crime that is inconsistent with and eliminates the possibility that the conviction was for a disqualifying crime.

This statutory burden of proof is not impossible, but can be difficult to shoulder. A negative premise can be proven if one can affirmatively prove a fact or set of facts that is inconsistent with or contradictory to the premise sought to be negated. Of course, inconsistent or contradictory facts must actually exist.

Furthermore, according to Clemente Avelino Pereida, Petitioner v. Robert M. Wilkinson, Acting Attorney General, at slip op. 8-11, establishing inconsistent or contradictory facts to prove the absence of a conviction for a disqualifying offense cannot be accomplished hypothetically by use of the categorical approach for classifying offenses.

For those unfamiliar with the technical meaning of “categorical approach,” the categorical approach originated as a hypothetical method for classifying an offense as an aggravated felony defined under section 101(a)(43) of the Act. It describes a direct comparison of the statutory elements of an offense (usually a State offense) to the statutory elements of a generic federal offense or federal offense referenced in the aggravated felony definition. If all of the elements of the offense under consideration match each of the elements in the generic federal offense or federal offense referenced in the aggravated felony definition there is no need for further inquiry. By use of inductive logic, a categorical match between the compared offenses exists. The categorical approach prohibits examination of the historical facts that constitute the offense under consideration.

The operative facts in the record under review in Clemente Avelino Pereida, Petitioner v. Robert M. Wilkinson, Acting Attorney General are as follows:

The Department of Homeland Security ("DHS") initiated removal proceedings against the Petitioner for entering and remaining in the United States unlawfully, which the Petitioner did not contest.

While his immigration proceedings were pending, the Petitioner was convicted of a crime under a Nebraska statue having multiple paragraphs describing different, distinct crimes. See Neb. Rev. Stat. §28–608 (2008).

Nevertheless, the Petitioner sought to establish his eligibility for cancellation of removal under 240A(b)(1) of the Act.

The Immigration Judge found that the Nebraska statute stated several separate crimes, some of which involved moral turpitude and one—carrying on a business without a required license—which did not.

Because Nebraska had charged the Petitioner with using a fraudulent social security card to obtain employment, the Immigration Judge concluded that the Petitioner’s conviction was likely not for the crime of operating an unlicensed business, and thus the conviction likely constituted a CIMT.

The Board of Immigration Appeals and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeal agreed with the Immigration Judge that the record did not establish which crime the Petitioner had been convicted of violating; but, because the Petitioner bore the burden of proving his eligibility for cancellation of removal, the ambiguity in the record meant he had not carried that burden and he was thus ineligible for cancellation of removal under section 240A(b)(1) of the Act. Pereida v. Barr, 916 F. 3d 1128, at 1131, 1133 (8th Cir. 2019).

In a nut shell, Justice Gorsuch reasoned that:

- The Act squarely places the burden of proof on the alien to prove eligibility for relief from removal. See section 240(c)(4)(A) of the Act;

- although a person could hypothetically violate the Nebraska statute without committing fraud, application of the categorical approach implicates two inquiries—one factual (what was the Petitioner’s crime of conviction?), the other hypothetical (could someone commit that crime of conviction without fraud?), and the party who bears the burden of proving these facts bears the risks associated with failing to do so;

- in order to tackle the hypothetical question of whether one might complete an offense of conviction without doing something that involved moral turpitude, a court must have some idea about what the actual offense of conviction is in the first place, and that requires examination of historical facts;

- It is not the place of the United States Supreme Court to choose among competing policy arguments; and

- Congress was entitled to conclude that uncertainty about an alien’s prior conviction should not yield a benefit.

It seems that some of the language in this opinion rejecting the categorical approach could have far reaching implications in terms of constraint for the expanding application of a hypothetical method (i.e. the categorical approach for classifying offenses) to classify offenses in immigration categories other than aggravated felonies.

In particular, the majority opinion points out that the Petitioner's argument based on the categorical approach "overstates the categorical approach’s preference for hypothetical facts over real ones." Clemente Avelino Pereida, Petitioner v. Robert M. Wilkinson, Acting Attorney General, at slip 8.

Use of the categorical approach to classifying CIMTs is an example of applying the categorical approach to categories other than aggravated felonies.

In my opinion, there are two reasons that a hypothetical approach for classifying crimes involving moral turpitude appears unlikely to stand the test of time.

First, unlike the definition of aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43) of the Act to which the hypothetical classification approach was first applied in immigration cases, it seems that Congress, by using the term, “moral turpitude,” intended for a decision maker to determine the nature of the behavior underlying an offense (as reflected by the elements of such offense proven beyond a reasonable doubt) for the purpose of assessing whether an alien is morally undesirable for admission, or whose presence in the United States is undesirable based on flawed moral character, or whether an alien is an undeserving beneficiary of benefits provided in the immigration laws; all based on behavior. Actual behavior is relevant to the exercise of discretion as well as classification of criminal offenses. These purposes dictated by statute are distinct from the purpose of disabling provisions that utilize the aggravated felony definition.

Aggravated felony classification consists of quantitatively matching the minimal definition of an offense by comparison to generic federal offenses found in or referenced in the definition of aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43) of the Act. The thrust of aggravated felony classification is not directly aimed at moral character or moral turpitude or behavior, but is strictly aimed at objectively identifying a specified crime labeled by Congress as an “aggravated felony.” The moral fiber of the individual convicted for an aggravated felony is irrelevant to the classification process or inquiry.

Even though an alien convicted for an aggravated felony cannot establish good moral character under section 101(f)(8) of the Act, aggravated felony classification does not require evaluation of criminal behavior based on the moral implications of such behavior. As previously noted, the definition of aggravated felony under section 101(a)(43) of the Act does not include moral turpitude as an element. Moreover, not all of the enumerated bars to establishing good moral character in section 101(f) of the Act share the same underpinning. For example, any alien convicted for simple possession of more than 30 grams of marihuana cannot establish good moral character under section 101(f)(3) of the Act.

Second, there is no generic definition of a crime involving moral turpitude containing any specific elements with which to compare any State or federal offense.

These are two reasons why I believe application of the same hypothetical aggravated felony classification method to the classification of crimes involving moral turpitude will not and should not survive over time. Perhaps, the reader can think of other reasons that support this assessment or might disagree. Only time will tell.

Returning to Clemente Avelino Pereida, Petitioner v. Robert M. Wilkinson, Acting Attorney General, the primary practical lesson that practitioners should remember is that the party that carries the burden of proof bears the risks associated with failing to do so.

For example, if the Petitioner in Avelino Pereida, Petitioner v. Robert M. Wilkinson, Acting Attorney General, could have proved that factually he had been convicted for carrying “on any profession, business, or any other occupation without a license, certificate, or other authorization required by law” under Neb. Rev. Stat. §28–608 (2008) he would have proven that he had not been convicted for an offense classified under sections 212(a)(2), 237(a)(2), or 237(a)(3)" of the Act, including any offense classified as a CIMT.

The moral of the story? It is possible and sometimes necessary to prove a negative for the party who bears the burden of proof in immigration proceedings.