Circular Reasoning in the Context of Asylum Claims

In a major administrative case that serves as an example of circular reasoning involving a particular social group and the motive of the alleged persecutor (i.e. the government of El Salvador), the Board of Immigration Appeals (“BIA”) determined that, even when an asylum applicant credibly establishes membership in a group defined by any number of immutable characteristics (e.g. sex, color, kinship ties, or a shared past experience fundamental to individual identity) that is at risk of some specific kind of punishment or harm in the country of his or her nationality or last country of habitual residence, this, without more, does not establish a risk of persecution that will support an asylum claim. Matter of Sanchez and Escobar, 19 I&N Dec. 276 (BIA 1985). This is still good law.

The asylum applicant must take one more step to prove that the risk of punishment or harm is on account of the group’s immutable characteristics. Specifically, the BIA ruled that:

. . . it is not enough to simply identify the common characteristics of a statistical grouping of a portion of the population at risk, but . . . there must be a showing that the claimed persecution is on account of the group's identifying characteristics.

See Matter of Sanchez and Escobar, 19 I&N Dec. 276, at headnote 6.

In Matter of Sanchez and Escobar, the asylum applicants asserted that:

they have a well-founded fear of persecution if returned to El Salvador on the basis of their “membership in a particular social group,” comprised of young (18 to 30 years of age), urban, working-class males of military age who have not served in the military or otherwise affirmatively demonstrated their support for the Government of El Salvador.

See Headnote 5.

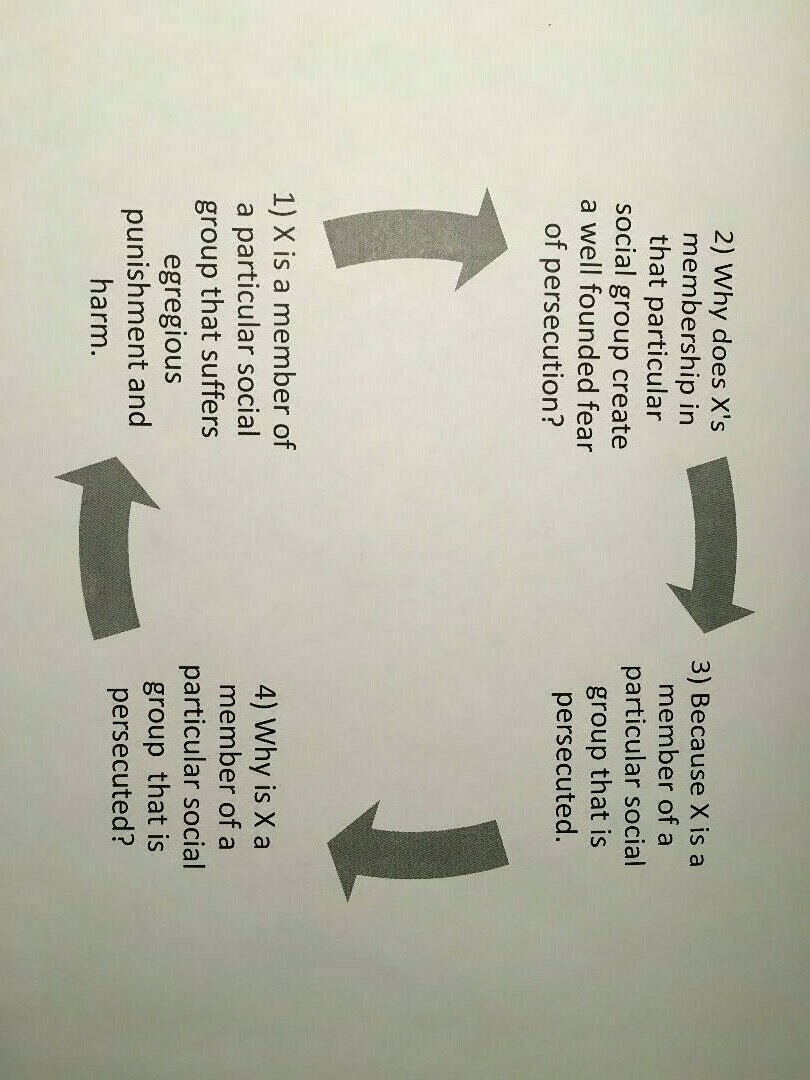

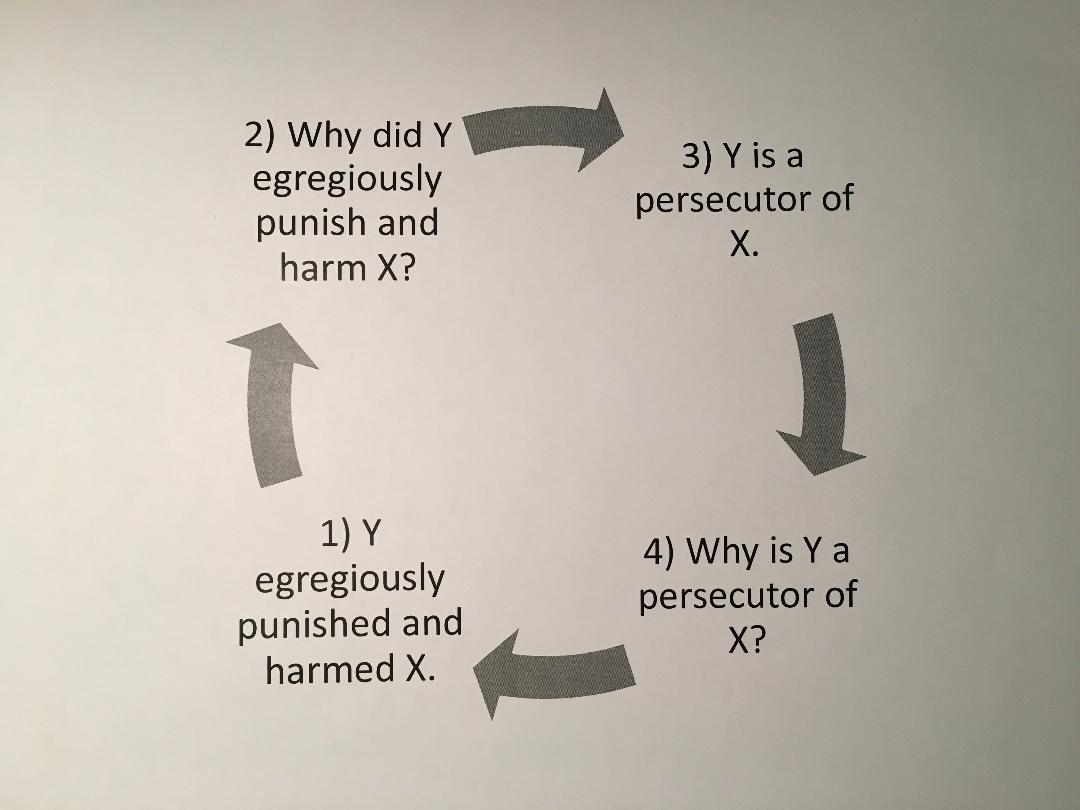

The asylum claim in Matter of Sanchez and Escobar failed primarily because the applicants relied entirely on circular reasoning.

Based on the facts of record, the particular social group of the applicants was clearly at greater risk of harm than the general population of El Salvador. However, the circular reasoning of the applicants' claim (that the particular social group was statistically at greater risk of harm than other El Salvadorans and was therefore persecuted) omitted sufficient evidence to conclude that the applicants' particular social group was targeted for harm on account of the group's immutable characteristics (i.e. "young (18 to 30 years of age), urban, working-class males of military age . . .").

According to the rationale articulated by the BIA in Matter of Sanchez and Escobar, the facts of record did not establish the required nexus between a persecutory motive of the alleged persecutor and the characteristics of the asylum applicants’ particular social group. See also Rreshpja v. Gonzales, 420 F.3d 551, at 555-56 (6th Cir. 2005) (stating that “a social group may not be circularly defined by the fact that it suffers persecution”).

More recently, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal reasoned in a published decision that:

- The Petitioner’s assertion that, but for her familial relationship with her brother, she would not have investigated his disappearance and the Zetas would not be threatening her fails because the assertion rests entirely on the motivations of the Petitioner, instead of the alleged persecutor.

- The nexus test requires determination of whether the protected ground is one central reason motivating the persecutor, not the persecuted.

- With regard to the actual motive of the alleged persecutor in the record under review, the threats or attacks motivated by criminal intentions do not provide a basis for protection under asylum law. See Thuri v. Ashcroft, 380 F.3d 788, at 793 (5th Cir. 2004).

- Finally, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal reasoned that under the nexus test, the Petitioner’s alleged protected trait—her particular social group—is, at best, incidental, tangential, superficial, or subordinate to another reason for harm, and not one central reason for the feared persecution.

See Edith Nohemi Vazquez-Guerra; Wendy Chantal Barragan-Vazquez, v. Merrick Garland, at pp. 2-9 (5th Cir. July 29, 2021) No. 18-60828.

As noted in previous posts, the challenge of establishing a nexus between the motivation of the alleged persecutor and the alleged particular social group will not go away, regardless of changing immigration policies of the exective branch of government. See INS v. Zacarias, 570 U.S. 478 (1992).

The United States Supreme Court clarified the distinction between persecutor agenda and specific motive for persecution in INS v. Zacarias, 570 U.S. 478 (1992). In the Zacarias decision, the United States Supreme Court determined that a guerrilla organization’s attempt to force Zacarias into military service did not, without more, establish persecution based on Zacarias’ political opinion, even though Zacarias was politically opposed to the guerrillas.

According to INS v. Zacarias, a victim of coercive recruitment must establish that the victim has been targeted because of the victim’s political opinion, and that the persecution is not solely the consequence of the guerrillas’ agenda to increase their ranks to carry out a war with the government or pursue their political goal; the guerrillas’ political goal being irrelevant. In other words, an asylum applicant claiming persecution on account of political opinion must tie punishment or harm to the asylum applicant’s political opinion, rather than solely establish that asylum applicant was a victim of the persecutor’s pursuit of the persecutor’s political agenda. If the asylum applicant only establishes egregious punishment or harm and opposition to the political goals of the persecutor, without more, he or she has not established eligibility for asylum.

Side stepping the imputation of circular reasoning when formulating particular social groups and establishing egregious punishment or harm or a well founded fear of egregious punishment or harm that will justify an asylum claim should always be in the mind of litigators who are representing asylum applicants.

The REAL ID Act, codified at section 208(b)(1)(B)(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended (“the Act”) requires that an asylum applicant or withholding of removal applicant "must establish that race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion was or will be at least one central reason for persecuting the applicant." [emphasis added] See section 101(a)(3) of the REAL ID Act of 2005; Pub. L. No. 109-13, Div. B, 119 Stat. 231 (2005).

The BIA has held that the REAL ID Act amendments relating to the burden of proof for asylum applications also govern applications for withholding of removal under section 241(b)(3)(A) of the Act. Matter of C-T-L-, 25 I&N Dec. 341 (BIA 2010).

No matter what kind of protected ground under section 101(a)(42)(A) of the Act or what kind of egregious harm or punishment forms the foundation for a persecution claim, the claimant must reach outside the convenient, but dubious, pattern of circular reasoning to adduce evidence that establishes cause and effect between the motive of the alleged persecutor as a central reason for alleged persecution linked to the race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion of the claimant and egregious punishment or harm.

More than one central reason for punishment or harm inflicted or intended by an alleged persecutor is possible. So be sure to focus and if necessary accentuate the central reason that is linked to at least one protected ground attributable to the claimant.

What is a central reason for persecution?

Decision makers at all levels will try to assign meaning to “central reason.”

For example, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal simply asks “why [the applicant], and not another person, was threatened” or harmed. Alvarez Lagos v. Barr, 927 F.3d 236, at 250 (4th Cir. 2019). See also Cruz v. Sessions, 853 F.3d 122 (4th Cir. 2017) (concluding that "the BIA and IJ applied an improper and excessively narrow interpretation of the evidence relevant to the statutory nexus requirement").

On the other hand, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal specifically disagreed, in part, with Cruz v. Sessions and denied a similarly situated Petitioner’s appeal because her particular social group was, at best, “incidental, tangential, superficial, or subordinate to another reason for harm,” not one central reason for the feared persecution. Edith Nohemi Vazquez-Guerra; Wendy Chantal Barragan-Vazquez, v. Merrick Garland, at 9 (5th Cir. July 29, 2021) No. 18-60828 (citing Sealed Petitioner v. Sealed Respondent, 829 F.3d 379, at 383 (5th Cir. 2016)). See also Sharma v. Holder, 729 F.3d 407, at 411 (5th Cir.2013); Shaikh v. Holder, 588 F.3d 861, at 864 (5th Cir.2009).

It is the responsibility of litigators to develop a factual record that will best support their clients' persecution claims.

Be sure to know how the concept of "central reason" for persecution is applied in your jurisdiction and introduce facts into the record of proceedings that are consistent with that application.