An Approved Visa Petition Does Not Guarantee Success For Adjustment Applicants

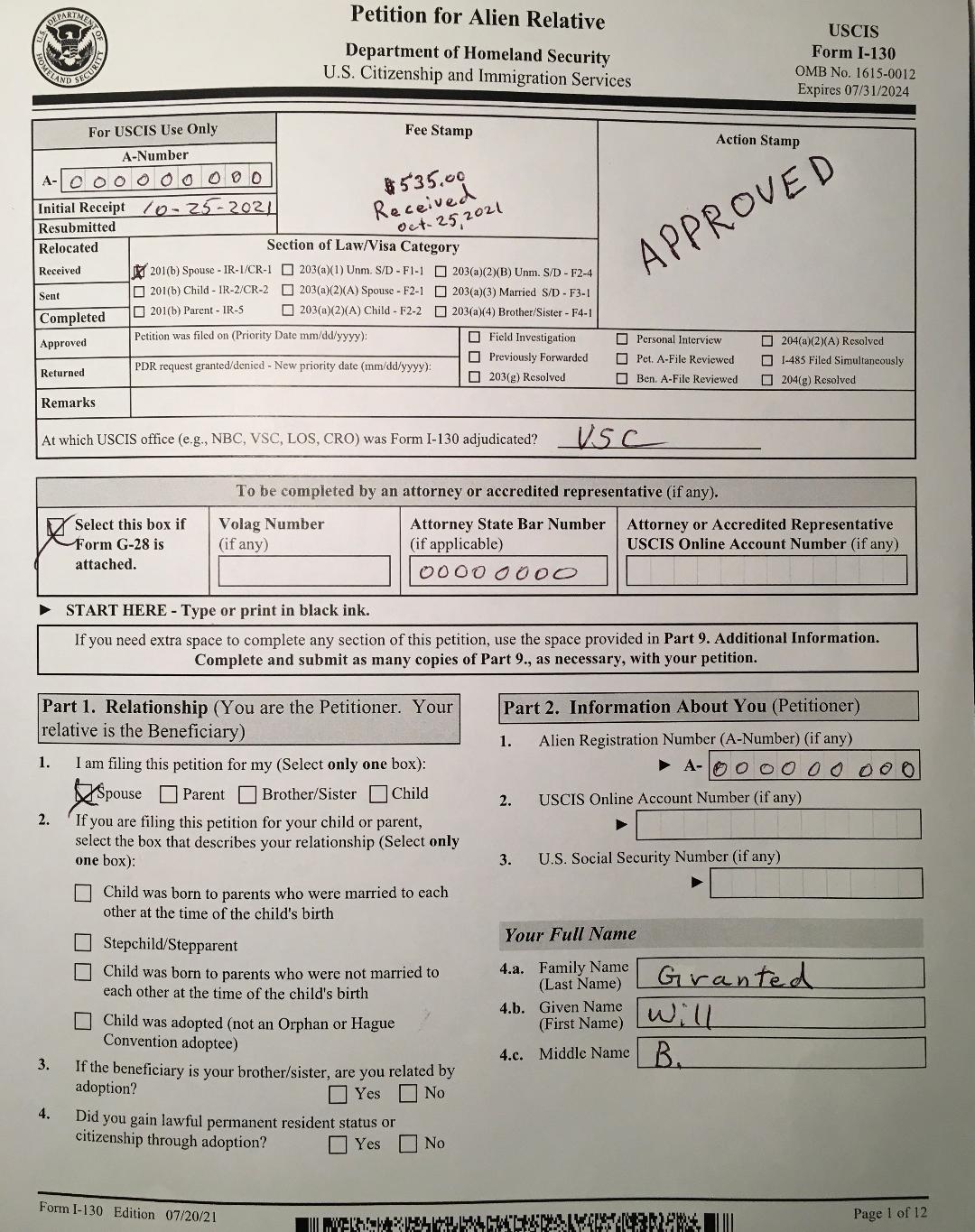

On October 13, 2021, The Board of Immigration Appeals ("BIA") published a precedent decision relating to adjustment of status under section 245(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended ("the Act") in which it held that an Immigration Judge has the authority to inquire into the bona fides of a marriage when considering an application for adjustment of status under section 245(a) of the Act, and deny the adjustment of status application based on a determination that the adjustment applicant has not established a bona fide marriage, even after the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) had approved the Form I-130 visa petition filed in support of the adjustment of status application. See Matter of Kagumbas, 28 I&N Dec. 400 (BIA 2021).

The procedural history, facts of record, holding and rationale in Matter of Kagumbas, 28 I&N Dec. 400 (BIA 2021) are as follows:

Case History

The DHS served the respondent with a notice to appear charging him with deportability pursuant to section 237(a)(1)(B) of the the Act for remaining in the United States longer than permitted.

The respondent conceded the charge, but filed an application for adjustment of status with the Immigration Court.

January 10, 2018, an Immigration Judge denied the respondent’s adjustment of status application under section 245(a) of the Act.

The respondent filed a notice of appeal.

Facts

The respondent is a native and citizen of Kenya who was admitted to the United States as a nonimmigrant F-1 student on August 26, 2006.

The respondent’s nonimmigrant status was terminated on October 17, 2007. Nevertheless, He remained in the United States without authorization.

The respondent conceded the charge based on section 237(a)(1)(B) of the Act for remaining longer than permitted, but filed an application for adjustment of status under section 245(a) of the Act with the Immigration Court.

The respondent based his adjustment of status claim on his marriage to a United States citizen whom he married on July 23, 2013.

The Immigration Judge concluded that the respondent’s marriage to his wife was not bona fide, and denied the respondent adjustment of status because “the marriage was entered into solely to confer an immigration benefit.”

Held

Appeal dismissed in part

Sustained in part

Remanded

Rationale

According to the BIA:

- Section 245(a) of the Act provides that the Attorney General may, in the exercise of discretion, adjust the status of an applicant who was inspected and admitted or paroled into the United States to that of a lawful permanent resident. The applicant must file an application for adjustment of status, must be eligible to receive an immigrant visa that is immediately available, and must be admissible to the United States.

- An applicant for adjustment of status has the burden of proof, which includes showing eligibility for the requested relief. See section 240(c)(4)(A)(i) of the Act (stating that an applicant applying for relief or protection has the burden to satisfy “the applicable eligibility requirements”).

- Immigration Judges have exclusive jurisdiction over applications filed for adjustment of status by respondents in removal proceedings (with the exception of “arriving aliens” according to 8 C.F.R. § 1245.2(a)(1)(i), (ii)).

- The Immigration Judge must “determine whether or not the testimony is credible, is persuasive, and refers to specific facts sufficient to demonstrate that the applicant has satisfied the applicant’s burden of proof.” See section 240(c)(4)(B) of the Act.

- The Immigration Judge’s assessment of whether the respondent has met his burden of proof does not become a mere ministerial act simply because an approved I-130 visa petition exists.

- If the respondent were not in removal proceedings and exclusive jurisdiction over his application rested with the DHS, there would be no credible claim that the approved I-130 visa petition prohibited the DHS from considering the bona fides of the marriage as part of the adjustment of status application.

- Therefore, an Immigration Judge must have the same authority by virtue of the exclusive jurisdiction to adjudicate an adjustment of status application.

- Decisions in two circuit courts of appeal support the BIA’s conclusion. Wen Yuan Chan v. Lynch, 843 F.3d 539, at 541 (1st Cir. 2016) (“the bona fides of the anchoring marriage were properly before the immigration court”); Agyeman v. INS, 296 F.3d 871, at 879 n.2 (9th Cir. 2002) (“The approved I-130 provides prima facie evidence that the alien is eligible for adjustment as an immediate relative of a United States citizen . . . However, we reject Agyeman's argument that no other evidence of the marriage is ever necessary.”).

- No court of appeal has reached a contrary conclusion.

See Matter of Kagumbas, 28 I&N Dec. 400, at 403-405 (BIA 2021).

Commentary

Some readers might be familiar with the 1972 decision in Matter of Bark, 14 I&N Dec. 237 (BIA 1972), rev’d on other grounds by Bark v. INS, 511 F.2d 1200 (9th Cir. 1975). I can almost guarantee that DHS attorneys are aware of Matter of Bark.

In Matter of Bark, at 240, the BIA held that “this Board and the special inquiry officers are not bound by [a] prior determination of a visa petition that an alien is entitled to a particular classification.”

In Matter of Bark, the Special Inquiry Officer (a title changed to “Immigration Judge” as of 1996 - Pub. L. 104–208, §371(b)(9)) denied the adjustment application in the exercise of discretion. See Matter of Kagumbas, at 405.

The significance of Matter of Kagumbas is that the BIA has now declared that, in spite of an approved I-130 petition based on an assessment by the DHS that the adjustment applicant had entered into a bona fide marriage, the Immigration Judge can deny an adjustment of status application not only in the exercise of discretion, but also for failure to establish a bona fide marriage as a necessary criterion for adjustment of status.

So what does this mean for the immigration practitioner who is representing a client in immigration proceedings?

In my experience, an adjustment of status applicant in removal proceedings whose Form I-130 visa petition has been approved by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”) is usually faced with a choice of requesting a hearing to consider the adjustment of status application before the Immigration Judge or seeking termination of removal proceedings to seek adjudication of the adjustment of status application by the USCIS.

This choice is recounted in Matter of Kagumbas, at 401, as follows:

[T]he Immigration Judge offered the respondent the option of a hearing on the adjustment application in Immigration Court in July or termination of proceedings so that the respondent could pursue adjustment with the USCIS. The respondent, through counsel, elected to pursue his adjustment of status application in Immigration Court, because the Immigration Court could hear the request sooner.

Due to back logs, USCIS adjudications can produce long delays. Even though clogged immigration court dockets produce results that fall far short of immediate gratification, Immigration Judges are likely to perceive a straight-forward adjustment application (i.e. an adjustment application with an approved Form I-130 visa petition that is uncomplicated by waiver applications needed to overcome inadmissibility) as an easy case that will not take much time to complete.

While on the bench, I would squeeze “straight-forward” adjustment hearings into half hour time slots to accommodate the adjustment applicant if no ominous cloud of doubt was readily visible on the horizon.

Generally speaking, a decision on an adjustment of status application in immigration court is likely to be obtained more quickly than returning to the USCIS queue.

It seems that Matter of Kagumbas, highlights the risk of asking a new adjudicator, to consider an adjustment application, instead of the USCIS which had already approved the Form I-130 visa petition based on a bona fide marriage.

Perhaps, if Kagumbas had been willing to wait for the USCIS his adjustment application would have been granted.

There is no way to know.

The reason for remand of the record of proceedings to the Immigration Judge in Matter of Kagumbas is unrelated to its legal precedent, but deserves comment.

The word, "indiscernible" in a transcript can provoke feelings ranging from annoyance, frustration and even anger for Immigration Judges and parties, especially after long hours dedicated to creating the record of proceedings. It's not unlike creating e-mails or text messages on your cell phone that the audio application misinterprets, but you can't change it!

One way for immigration practitioners to avoid "indiscernible" gaps in the record of proceedings is simply to remember that your purpose as a legal representative in litigation is to create and preserve the record of proceedings which is essential to a client's due process interests. Creating a record of proceedings requires a methodical and deliberate approach.

While on the record, it helps to remember that you are not arguing or squabbling with your spouse or your friend. You are making a recording. Therefore, slow down and be methodical about articulating a legal position, responding to opposing counsel and questioning witnesses. If a witness is mumbling or speaking sotto voce or in a low volume ask them to slow down or speak up. Always keep in mind the importance of capturing the moment for an accurate record of proceedings. Obviously, Immigration Judges need to attend to accurate record creation and preservation as well.

I have seen transcripts in which negative statements are changed to positive statements by omitting "no" or "not" from the sentence. This can be worse than "indiscernible!" Aberrations like this need to be brought to the attention of the Immigration Judge by filing a motion to correct the transcript before the record of proceeding is forwarded to the BIA for appellate review.

In Matter of Kagumbas, the witness may have been mumbling. See Matter of Kagumbas, at 406-407. Problems of this sort seem to occur when the witness is speaking in English without the benefit of an interpreter. Interpreters employed for languages other than English usually ensure clarity and accuracy.

Words are insufficient to express the appreciation and respect that I have acquired for interpreters who labor to capture the colloquy of the courtroom upon which the record of proceedings is founded. The integrity of the record created through professional and competent interpreters is truly a measure of the integrity of our immigration courts.

To gain insight about the function of an interpreter, try watching or listening to a news broadcast. Repeat in the same language, without interpretation, exactly what is being said, either simultaneously or consecutively. Chances are that you will soon be stumped. Repeating exactly what is being said is what interpreters are expected to do during a removal hearing, except the interpreters are converting one language to another. Since translation, rather than interpretation, is the goal in court proceedings, the title, “interpreter,” seems to be a misnomer. Interpreters do not enjoy the luxury of improving or altering the form or content of statements. Attorneys should, therefore, strive to simplify questions as much as possible. Keep it short and sweet and you’ll not only be appreciated by the interpreter; you’ll leave a clear record for future briefing and appellate review.

That being said, if you disagree with an interpretation of testimony during a hearing don't hesitate to object. When confronted with this sort of objection as an Immigration Judge, I would ask what the objecting party thinks the interpretation should be. Then I would ask the interpreter if the interpreter accepts the proposed interpretation change. If the interpreter accepted the change everyone benefited from the correction of the record. If the interpreter stood by the original interpretation, at least the objection was captured in the record. Usually, this sort of conflict can be clarified and resolved by follow up questions.

Failure to address articulation issues during a hearing can, as demonstrated in Matter of Kagumbas, result in remand or possibly affect the outcome of the proceedings.