A Form I-213 is Probative Evidence of Notice if The Notice to Appear is Missing

The procedural history, facts of record, holding and rationale in Alexandre-Matias v. Garland (June 13, 2023) No. 21-60798 are as follows:

Case History

An Immigration Judge ordered the Petitioner removed in absentia (i.e. an order issued by an Immigration Judge in the absence of the individual whom the federal government is seeking to remove, deport or exclude from the United States).

The Petitioner filed a motion to reopen removal proceedings.

The Immigration Judge denied the Petitioner’s motion to reopen.

The Petitioner appealed the denial of her motion to reopen to the Board of Immigration Appeals (“BIA”).

The BIA dismissed the Petitioner’s appeal.

The Petitioner filed a petition for review of the decision the BIA.

Facts

- The Petitioner is a native and citizen of Brazil who was ordered removed in absentia in 2005.

- In 2018, the Petitioner moved to reopen and rescind the removal order.

- An Immigration Judge denied the Petitioner’s motion to reopen.

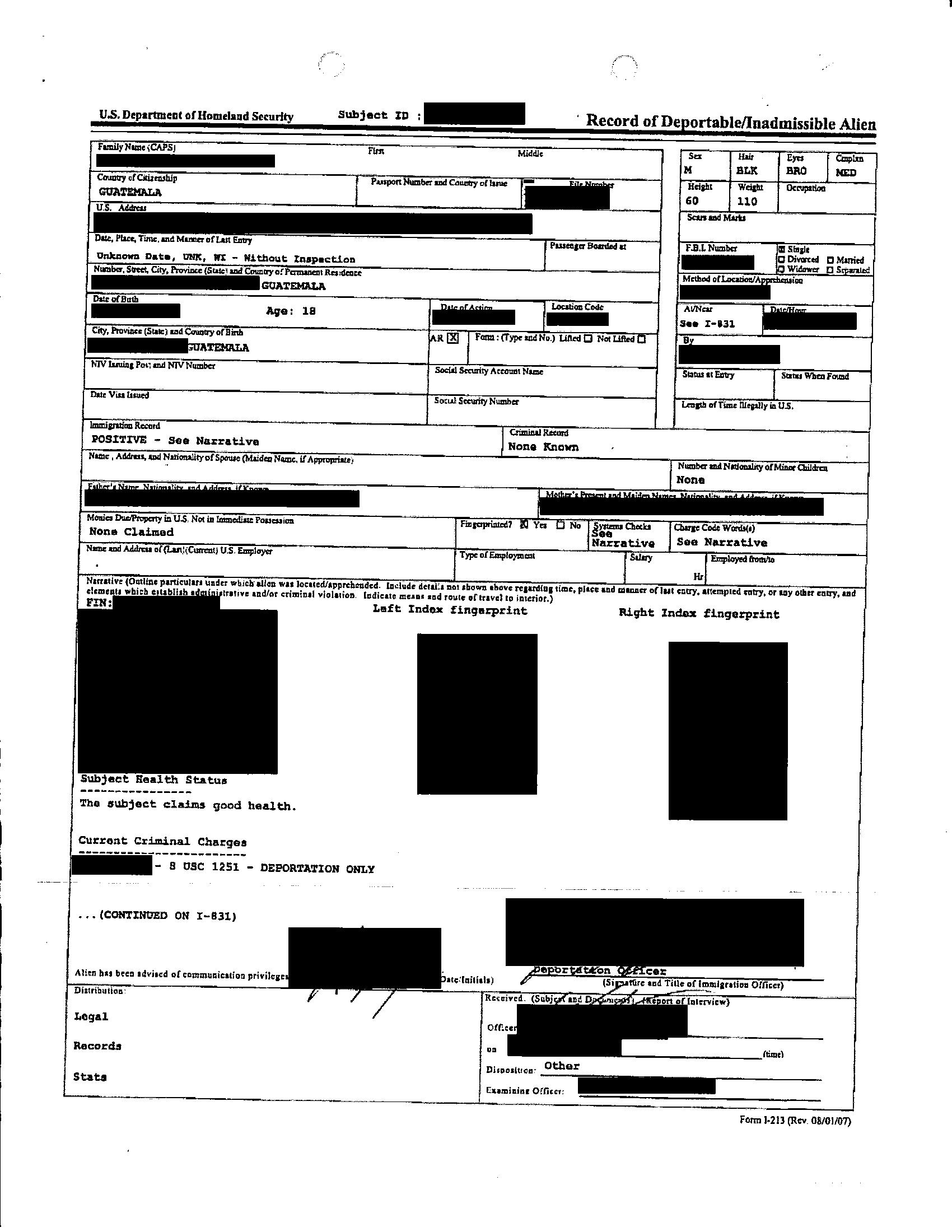

- The BIA, relying on a Form I-213, the Record of Deportable/Inadmissible Alien relating to the Petitioner in a reconstituted record that did not include the Petitioner’s notice to appear (“NTA”), dismissed his appeal.

- The Form I-213 reflected that an interpreter was provided and assisted in the NTA paperwork and recorded the address where the Petitioner planned to live.

Held

Petition for Review DENIED

Rationale

The Petitioner raised four challenges to the BIA’s denial of his motion to reopen:

- The BIA and the Immigration Judge lacked jurisdiction over his removal proceedings because the record does not show that his NTA was ever filed with the immigration court, as required by 8 C.F.R. § 1003.14(a).

- The BIA erred by relying on a reconstructed record that did not contain his NTA.

- His in absentia removal order should have been rescinded because he did not receive written notice of the time and place of his removal hearing, as required by section 239(a)(1)(G)(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended (“the Act”) and as permitted in section 240(b)(5)(C)(ii) of the Act.

- That the BIA violated his due process rights by denying his motion to reopen in the absence of notice of his removal hearing.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal reasoned as follows:

- With regard to the Petitioner’s jurisdictional claim: 8 C.F.R. § 1003.14 “is not jurisdictional,” but is “a claim-processing rule.” Pierre-Paul v. Barr, 930 F.3d 684, at 691 (5th Cir. 2019), abrogated in part on other grounds by Niz-Chavez v. Garland, 141 S. Ct. 1474, at 1479–80 (2021). See Maniar v. Garland, 998 F.3d 235, at 242 n.2 (5th Cir. 2021) (confirming that Pierre-Paul’s jurisdictional holding remains good law).

- With regard to the Petitioner’s assertion of error based on the BIA’s reliance on a Form I-213 in a reconstructed record that did not contain his NTA:

-

-

- A Form I-213 may be used to establish an alien’s deportability. See Bustos-Torres v. INS, 898 F.2d 1053, at 1058 (5th Cir. 1990).

-

Nothing in the record suggests that the Petitioner’s Form I-213 “is incorrect or was obtained by coercion or duress.” Matter of Ponce-Hernandez, 22 I&N Dec. 784, at 785 (BIA 1999); see also Matter of Barcenas, 19 I&N Dec. 609, at 611 (BIA 1988) (describing a Form I-213 as an “inherently trustworthy” document).

-

-

- With regard to the Petitioner’s claim that his in absentia removal order should have been rescinded because he did not receive written notice of the time and place of his removal hearing:

- the Petitioner’s Form I-213 references the time, date, and location of the scheduled removal hearing and records that the Petitioner was provided with the “necessary forms to affect [sic] the NTA,” as well as a certified interpreter to translate the NTA paperwork which led to the BIA’s conclusion that had been personally served with an NTA, advised of the time and place of his removal hearing, and afforded a Portuguese interpreter.

- The Petitioner failed to present such compelling evidence that no reasonable factfinder could conclude against the BIA’s conclusion. See Wang v. Holder, 569 F.3d 531, at 536–37 (5th Cir. 2009).

- Therefore, the BIA did not abuse its discretion in dismissing the Petitioner’s appeal from the denial of his motion to reopen.

- With regard to Petitioner’s claim that the BIA violated his due process rights by denying his motion to reopen in the absence of notice of his removal hearing:

- The Petitioner asserted a due process challenge to the discretionary denial of his motion to reopen, his claim fails for lack of a liberty interest. See Ramos-Portillo v. Barr, 919 F.3d 955, at 963 (5th Cir. 2019).

- To the extent the Petitioner asserted a due process challenge relating to his purported failure to receive notice of his scheduled removal hearing, he must initially to show substantial prejudice by making “a prima facie (i.e. on the face or surface of the record) showing that the alleged violation affected the outcome of the proceedings.” Okpala v. Whitaker, 908 F.3d 965, 971 (5th Cir. 2018).

- The BIA did not commit reversible error by concluding that the Petitioner failed to establish his purported problems understanding the interpreter caused him substantial prejudice by preventing him from discovering his hearing date.

- Therefore, the Petitioner failed to establish substantial prejudice based on any due process violation that affected the outcome of his removal proceedings.

Commentary

Due Process

Due process in immigration proceedings is governed by section 240(b)(4) of the Act. In short, an alien subject to immigration court proceedings is entitled to:

- the “privilege of being represented, at no cost to the Government, by counsel;”

- “a reasonable opportunity to examine the evidence against the alien;”

- “to present evidence on the alien’s own behalf;”

- “to cross-examine witnesses presented by the Government;” and

- “a complete record shall be kept of all testimony and evidence produced at the proceedings.”

This statutory prescription for due process in immigration court proceedings is commonly described as “fundamental fairness.” For this reason, Constitutional challenges to due process in immigration court proceedings that leap over the specific statutory and regulatory foundations for fundamental fairness do not gain traction in the federal courts. See, for example, Alimi v. Ascroft, 391 F.3d 888, at 890 (7th Cir. 2004) (“[T]he statutes and rules require fair hearings, and it is inappropriate to bypass these non-constitutional grounds for decision” by raising a “gratuitous” “constitutional argument.”).

The requirement to demonstrate prejudice arising from the government’s failure to follow regulations is also well established. See, for example, Matter of Garcia-Flores, 17 I&N Dec. 325 (BIA 1980) (Evidence obtained in violation of a regulation can be “excluded . . . where the regulation in question serves a purpose of benefit to the alien and the violation prejudiced interests of the alien . . .”).

Form I-213

Challenges to the Form I-213 as evidence extend back in time well beyond Matter of Ponce-Hernandez and Matter of Barcenas, cited by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal in Alexandre-Matias v. Garland (June 13, 2023) No. 21-60798.

The BIA published the following determination in 1976:

Absent proof that the Form 1-213 contains information that is incorrect or which was obtained by coercion or force, that document is inherently trustworthy and would be admissible even in Court as an exception to the hearsay rule as a public record and report under Rule 803(8) of the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Matter of Mejia, 16 I&N Dec. 6 (BIA 1976).

Unless the information in a Form I-213 was obtained by means of egregious conduct on the part of the officers or officer that obtained the information, the chances of suppressing the Form I-213 or its contents are slim.

Standard of Review For Motions to Reopen

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal reviews denials of motions to reopen “under a highly deferential abuse-of-discretion standard.” Fuentes-Pena v. Barr, 917 F.3d 827, at 829 (5th Cir. 2019). Specifically, a discretionary BIA decision relating to a motion to reopen will not be disturbed “so long as it is not capricious, racially invidious, utterly without foundation in the evidence, or otherwise so irrational that it is arbitrary rather than the result of any perceptible rational approach.” Yu Zhao v. Gonzales, 404 F.3d 295, at 304 (5th Cir. 2005).

Obviously, the abuse-of-discretion standard is extremely high. Even an artless or inappropriate administrative decision might survive abuse-of-discretion review.

In Absentia Orders

Perhaps, a review of in absentia orders which are permanently linked with motions to reopen will be helpful to some readers.

No appeal is allowed in the case of an in absentia order. Filing a motion to reopen is the only way to challenge an in absentia order. See section 240(b)(5)(C) of the Act.

In my experience, motions to reopen hearings conducted in absentia account for a relatively large number of motions filed in immigration court.

The requirements of a motion to reopen and rescind an in absentia removal order are as follows:

- The motion must be filed within 180 days after the date of the removal order if the alien is seeking to demonstrate exceptional circumstances (defined under section 240(e)(1) of the Act) for failure to appear; or

- The motion may be filed without any time limit if the alien is seeking to demonstrate insufficient notice under section 239(a)(1) and (2) of the Act.

The filing of a motion to reopen and rescind an in absentia removal order stays the removal order while it is pending before the Immigration Judge.

It might be helpful to know that if the alien is seeking to demonstrate exceptional circumstances to justify reopening a fee is required. See 8 C.F.R. § 1003.24(b)(1).

If, however, the alien is seeking to demonstrate insufficient notice no fee is required. See 8 C.F.R. § 1003.24(b)(2)(v).

If the alien is seeking to demonstrate both exceptional circumstances and insufficient notice, I believe a fee is required under 8 C.F.R. § 1003.24(b)(2)(v).

Rejection of a motion by the immigration court because a required fee is not paid can result in the removal of an alien between the time of rejection and the time of proper filing. When the DHS deportation officer checks with the immigration court to verify whether a motion to reopen is pending, a computer check will indicate no motion pending. A rejected motion is not pending.